Download the full Dallas Report >

Located in north-central Texas, Dallas has a population of over one million and is the state’s third-largest city. Historically, the area was home to the Wichita, Comanche, Caddo, Cherokee, and Kiowa peoples. “In 1841, General Edward H. Tarrant led an armed expedition of Texans into the Three Forks area, bent on removing the last Indian residents… in order for the Republic to attract other Americans to settle in Texas.” Today, approximately 20,000 American Indians live in the Dallas-Fort Worth metro area.

The first white American farmers to settle in the Dallas area brought slaves with them, and by 1859 one out of every 10 people in the county was a Black slave. Dallas Truth, Racial Healing, & Transformation compiled historical narratives to lift up the erased or untold stories of Dallas’s origins, and details Dallas’s long history of “forced labor, violence, murder, rape, terrorism, torture, lynching, anti-Blackness and the dehumanizing and impoverished after-effects of the chattel slavery system such as Jim Crow laws”, none of which Dallas county or the City of Dallas acknowledges, despite Dallas having the largest chapter of the Ku Klux Klan.

Racist policies and practices shaped the segregated landscapes of major cities, including Dallas. During the 1930s, the Roosevelt administration created the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) to lend new mortgages refinance home mortgages that were at default during the Great Depression,). By 1936 the federal agency had provided one million new mortgages and owned one in five nationally. The HLOC developed lending risk maps in over 100 large cities and map-makers relied on the prejudices of local loan officers, city officials, appraisers and realtors in appraising sections of the city, rating white areas of town as “desirable” and “best” for lending and areas of town where Black people, immigrants, and Jewish people lived as “hazardous,” thereby curtailing lending or issuing loans at much higher interest rates.

Many Black and immigrant families who could not obtain fair mortgages were forced into contract sales, in which they sometimes paid double the worth of the home, could not build equity, and were more easily subject to eviction. Dallas adopted local racial zoning rules that decreed separate living areas for Black and white families and used public housing and Section 8 programs to perpetuate segregation. Many Black and immigrant families who could not obtain fair mortgages were forced into contract sales, which they paid sometimes double the actual worth of the home, could not build equity, and were more easily subject to eviction. HOLC maps knit segregation into the landscape, and today many of these historic maps align with metro-wide segregation and inequalities in homeownership. In Dallas, residential segregation patterns observable today align with redlining maps. (See Dallas’ HOLC map showing the “redlining” of neighborhoods throughout the city).

School segregation also undoubtedly determined intergenerational opportunity in Dallas. In 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld racial segregation and for the next 60 years Jim Crow laws legally defined schools, workplaces, buses, railroad cars, and even hospitals and cemeteries as either “white only” or “colored” (Plessy v. Ferguson). In Dallas, white officials also established segregation laws prohibiting Mexican Americans from attending the same theatres, parks, swimming pools, and schools as whites. White Texan officials further oppressed Mexican American children and adults by creating segregated schools for Mexican American children and passing English-only laws punishable by penalties, fines, and classroom shaming. In 1954, segregation was challenged in Brown v. Board of Education, and the Supreme Court held that the “separate but equal” doctrine violated the 14th Amendment. In a unanimous decision, Chief Justice, Earl Warren wrote, “In the field of public education, the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” English-only laws remained in place until 1973 when the Bilingual Education and Training Act was passed.

Subsequently, school desegregation plans were initiated in many cities, both in the South as well as in the North, where schools were often racially segregated though without the formal laws of the South. After the Brown decision, white officials and residents in Dallas passed laws that prohibited desegregation and empowered the governor to close schools to avoid it. The Dallas school superintendent was quoted in the fall of 1954 as saying the district “will not end segregation.” However, the Fifth Circuit Court ordered desegregation in 1961 to begin in Dallas, and efforts to make integration a reality continued unsuccessfully into the 1980s.

In 2003, Dallas was officially released from court oversight of desegregation, but schools continue to be racially concentrated: the average Latino student attends a school where 80% of their peers are Latino. Similarly, the average Black student attends a school where 50% of their peers are Black, and where 45% of their peers are Latino. In general, the northern part of the district is predominantly white, while other areas have more children of color. It’s not just racial differences within district schools but also those that exist between Dallas and nearby school districts, such as Highland Park, where 86% of children are white compared to Dallas which is predominantly students of color.

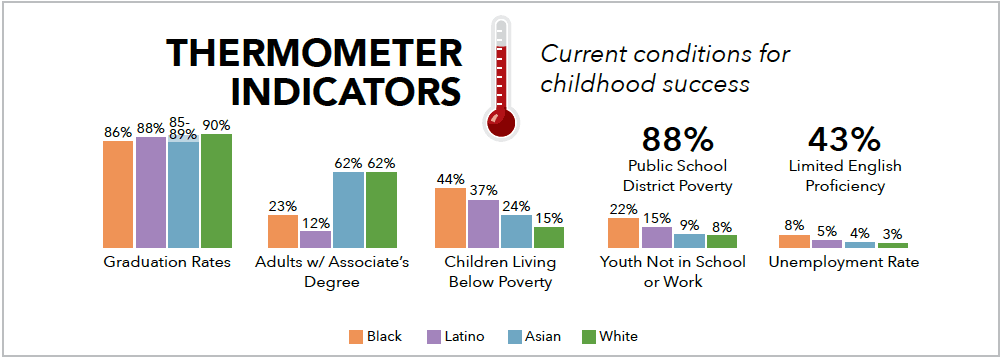

Dallas Independent School District is the 16th largest in the nation and the largest district in the state, serving 158,941 students in 230 schools, including 147 elementary, 35 middle, 38 high and 10 multi-level. Approximately 43% of students are English language learners. Latino students are 70% of the student population, Black 23%, white 5%, Asian 1%, and Native .3%. The percentage of low-income children in Dallas is 34%, but the percentage in the district is twice that (88%). The percent of Latino children in poverty is twice as high as white children, and for Black children it is nearly three times as high. The percentage of Black youth out of school and unemployed is three times that of white youth, and for Latino youth it is nearly twice that of white youth.

State of Healthy Living and Learning in Dallas

Overall, Dallas has large gaps in access to resources and supports across each of the domains, though major community-driven solutions and policy changes are showing promise. Of the cities studied, Dallas has the lowest rate of insured youth (85%), and some of the lowest rates of access to healthy food for low-income residents. As of the latest national reporting data from the 2015-16 school year, there were not any psychologists in the school system and only a few social workers for the entire district of 160,000 students. When it comes to neighborhood living environments, Dallas had basically no access to high-frequency public transportation, and one of the lowest levels of access to financial services (checking and credit services). Dallas does have the highest percentage of renters in affordable housing compared to other cities studied (55%), though inequity in wages is pronounced. 45% of Latino households and 55% of Black households do not earn enough wages for their labor to live above subsistence, while nearly 90% of white households do earn above that threshold.

Dallas and surrounding suburbs are also confronting the need to address racism and racial violence in the police department, particularly in the Black community following two recent high-profile cases where the police shot innocent Black people in their own homes. Botham Jean was shot and killed in his Dallas apartment by Officer Amber Guyger who reportedly entered his apartment mistaking it for her own, and Atatiana Jefferson also was shot and killed in her home in nearby Fort Worth by police responding to a non-emergency call from a neighbor who was concerned when they saw her front door standing open. This racist, over-policing of Black bodies is pervasive and goes much deeper than the stories that make national headlines. For example, in the 2015-16 school year Dallas public schools had the highest number of pre-school suspensions compared to other cities studied, all of which were Black or Latino children. House Bill 674 recently barred school districts in Texas from suspending students in pre-k through second grade under most circumstances, and in the past school year, out-of-school suspension for young students did drop significantly, though in-school-suspensions have generally remained high. However, a culture of policing Black and brown children even at the earliest ages has continued, and Black students in grades 3-12 still experience disproportionate in- and out-of-school suspensions that remove students from the classroom and create a school-to-prison pipeline, instead of taking a youth development approach like using restorative practices.

The Dallas Truth, Racial Healing, and Transformation (TRHT) Task Force is working to build relationships, narrative change, and policy change through deep community engagement across racial/ethnic groups and neighborhoods to create an inclusive city. “The TRHT approach examines how the hierarchy of human value became embedded in our society, both its culture and structures, and then works with communities to design and implement effective actions that will permanently uproot it.” Dallas TRHT hosted nearly a dozen community visioning sessions with Dallas-area residents and has developed a theory of change and cohort of community leaders to adopt a cross-sector approach to supporting youth and families. This comprehensive approach to changing systems led by Dallas TRHT is a best practice model for other cities seeking to end racism and a reminder that community-building work cannot be left out of the equation and must be resourced to bring about sustainable, long-term transformational change.

Dallas skyline by Ethene Lin.

For the data breakdown on every indicator, along with endnotes and references, download the PDF report below: