Download the full Atlanta Report >

Located in Northwest Georgia, Atlanta, the “city in the forest,” is the state capital and home to 500,000 residents, making it the 37th most populous city in the U.S. Aerospace and telecommunications are some of the city’s major industries. Before Atlanta’s 1847 incorporation, the Muscogee and Cherokee people presided over the region. The U.S. military violently removed many Native people during the 1830’s Trail of Tears, forcibly relocating 60,000 Native Americans to the west of the Mississippi River. Atlanta has been a place of profound racial struggle and resistance. It was a major geographic center of the civil rights movement and birthplace of prominent civil rights leaders including Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Racist policies and practices shaped the segregated landscapes of major cities like Atlanta. During the 1930s, the Roosevelt administration created the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) to lend new mortgages refinance home mortgages that were at default during the Great Depression,). By 1936 the federal agency had provided one million new mortgages and owned one in five nationally. The HLOC developed lending risk maps in over 100 large cities and map-makers relied on the prejudices of local loan officers, city officials, appraisers and realtors in appraising sections of the city, rating white areas of town as “desirable” and “best” for lending and areas of town where Black people, immigrants, and Jewish people lived as “hazardous,” thereby curtailing lending or issuing loans at much higher interest rates.

Many Black and immigrant families who could not obtain fair mortgages were forced into contract sales, in which they sometimes paid double the worth of the home, could not build equity, and were more easily subject to eviction. HOLC maps in Atlanta solidified segregation, and today that historic lending framework aligns with metro-wide inequalities in homeownership. (See Atlanta’s HOLC map showing the “redlining” of neighborhoods throughout the city.) Today’s residential demographic patterns, with more white people to the north and more people of color to the south, can be traced to redlined areas. In 1922, the Atlanta City Planning Commission zoned areas of the city as “white districts” and “colored districts,” saying that “race zoning is essential in the interest of public peace, order, and security” while also warning city officials that white areas needed to be protected from “encroachment of the colored race.” During the 1980s, white people in Atlanta secured home loans at five times the rate of Blacks, and race, not home value or household income, determined those lending patterns.

Educational suppression and segregation influenced intergenerational opportunities. Early in Georgia’s history, whites passed anti-literacy laws that prohibited Black people from reading and writing, punishable by death. In 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld racial segregation and for the next 60 years Jim Crow laws legally defined schools, workplaces, buses, railroad cars, and even hospitals and cemeteries as either “white only” or “colored” (Plessy v. Ferguson). In 1954, segregation was challenged in Brown v. Board of Education, and the Supreme Court held that “separate but equal” violated the 14th Amendment. In a unanimous decision, Chief Justice, Earl Warren wrote, “In the field of public education, the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” Subsequently, school desegregation plans were initiated in many cities, both in the South as well as in the North, where schools were often racially segregated even without the formal laws of the South.

After the Brown decision, whites in Atlanta resisted integration until 1961, when the courts threatened to close Atlanta schools for non-compliance. That year, nine Black students (“the Atlanta Nine”) integrated four all-white high schools and desegregation busing began. The city’s busing program ended in 1973. During and after Atlanta’s desegregation era, the city underwent dramatic demographic changes: white realtors steered white homebuyers to outlying suburbs and Black middle-class families left the city for neighboring DeKalb county, leaving a primarily low-income and majority Black population.

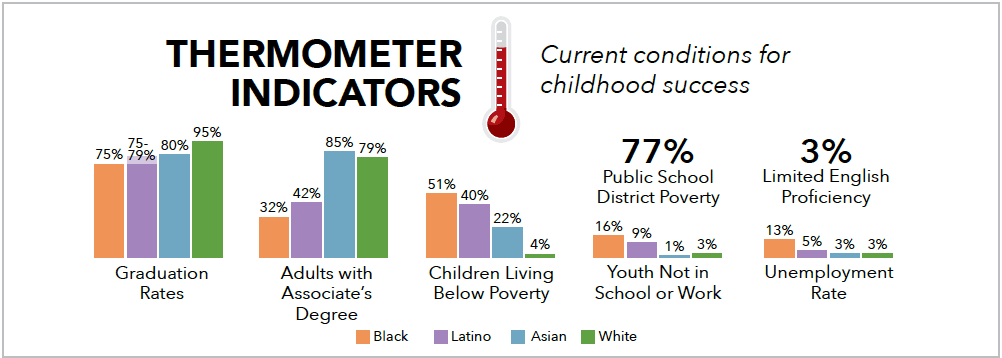

Presently, Atlanta Public Schools is among the 100 largest school districts nationally, enrolling 51,600 students and overseeing 96 traditional schools (55 elementary schools and 16 middle and 25 high schools) and 12 charter schools. The majority of students are Black (75%), 15% white, 7% Latino, and .2% Native American. The percent of children in poverty across the city is 35%, but the school district has over twice that: 77%. Three percent of students are English language learners. The percentage of Black children in poverty is 12 times that of white children and for Latino children, it is 10 times higher. The youth of color in Atlanta are more likely to be out of school and unemployed compared to white youth. Communities in Schools works in almost 40 Atlanta Public Schools, providing a site-based coordinator to implement a model of integrated student supports.

State of Healthy Living and Learning in Atlanta

Overall, Atlanta has large gaps in access to resources and supports across each of the domains, with large racial inequities in access. However, voter turnout is a bright spot in Atlanta, with 66% of voters casting votes in the 2018 mid-term elections compared to the national average of 50%. While change is needed, this demonstrates that people are civically engaged – a key ingredient for demanding change. When it comes to health equity, Latino children face large gaps in access to health insurance; and there is a dearth of supermarkets within walking distance of residents living in low-income census tracks, especially for Black residents. Additionally, Atlanta has far more infants born below birthweight compared to the national average, with large racial disparities between Black and Asian infants, and white infants; and youth mortality for Black children is more than double the rate of white children.

When it comes to Stability, like most other cities, Atlanta has major economic inequities in livable wages, with only 55% of Black families and 69% of Latino earning high enough wages for their labor to live above subsistence, compared to 95% of White families. At the same time, only half of all families in Atlanta have access to affordable housing, and the public transportation system is inadequate for most communities to rely on to get to where they need to go. In schools, nearly 20% of Black students in the city have received at least one in-school or out-of-school suspension – almost 10 times the rate of white suspensions, and there are not clear commitment or resources for restorative practices or anti-bullying.

Atlanta skyline by Flickr user London Looks.

For the data breakdown on every indicator, along with endnotes and references, download the PDF report below: